The video game industry is undergoing some dysfunction and disrepair of late. Despite Chinese games like Black Myth: Wukong selling well, and “free to play” gacha games like Star Rail, Wuthering Waves and Genshin Impact making decent money, western studios like Ubisoft and Bioware are imploding. Our first “AAAA game” was less than successful. Concord, meant to be the new Star Wars, performed poorly enough that it was pulled from the market in less than two weeks despite 8 years of production and many millions of dollars.

And then there’s Dustborn. It’s technically still available, but not selling well, and reviews are, well, mixed. As a case study, let’s compare it to Dust: An Elysian Tale and Dustforce DX. These comparisons will be somewhat apples to oranges, to be sure, but there’s still value in poking a bit at what these games are and how well they have been received.

Dustforce and Dust are each more than a decade old at this point, which has allowed them to accrue more word of mouth success than Dustborn. Dustforce is available primarily on PC and Mac, while Dust is available primarily on PC and XBox 360, though both were ported elsewhere.

Dustborn, being a more modern game from 2024, is available on PC, PS4, PS5, XBox One and XBox Series X/S.

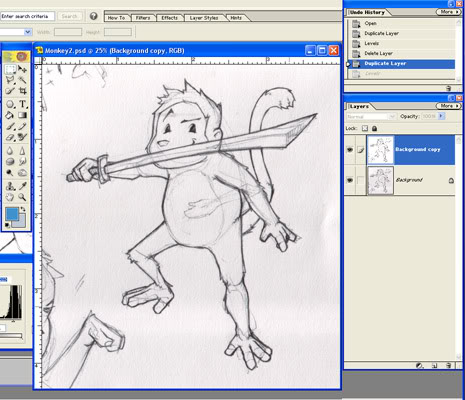

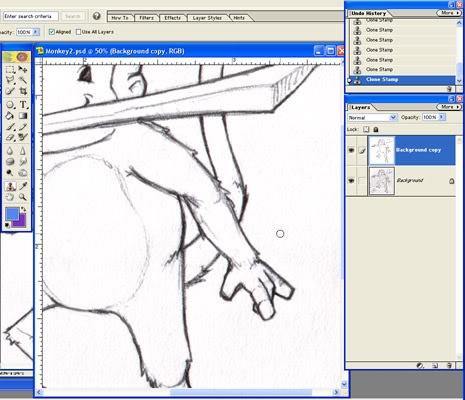

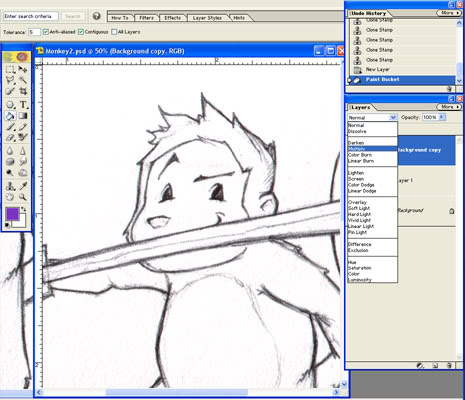

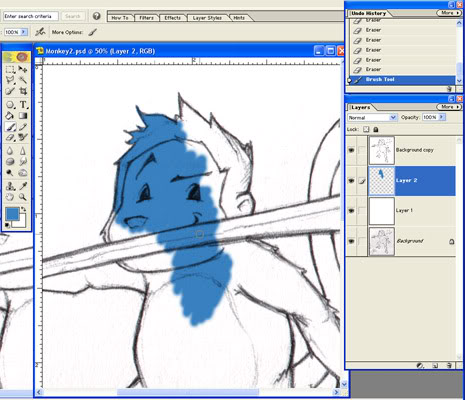

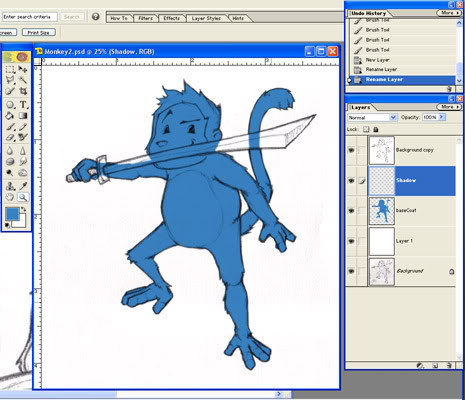

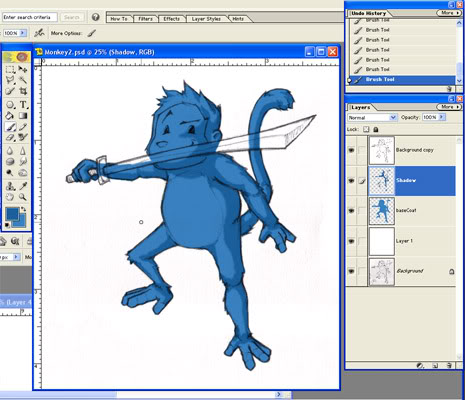

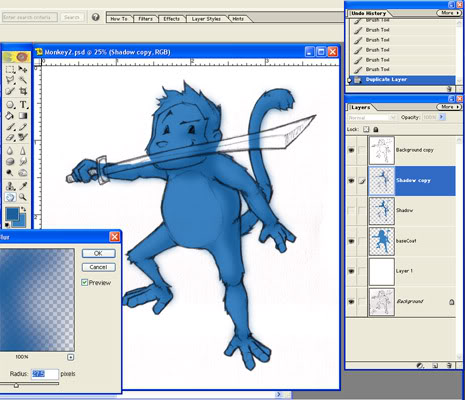

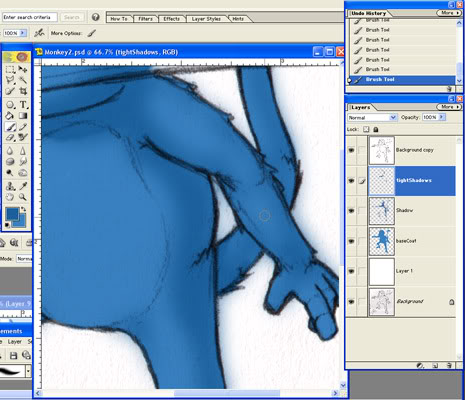

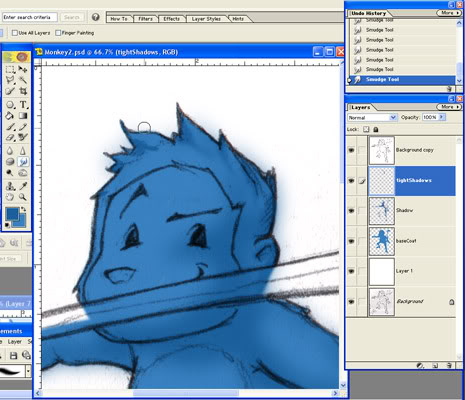

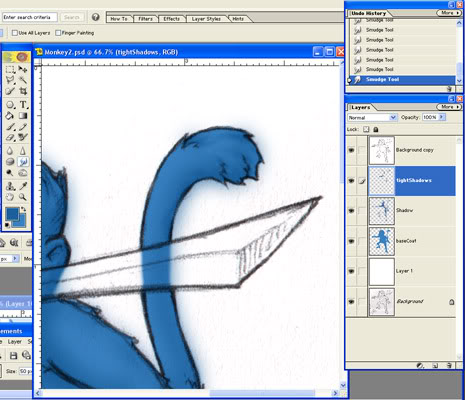

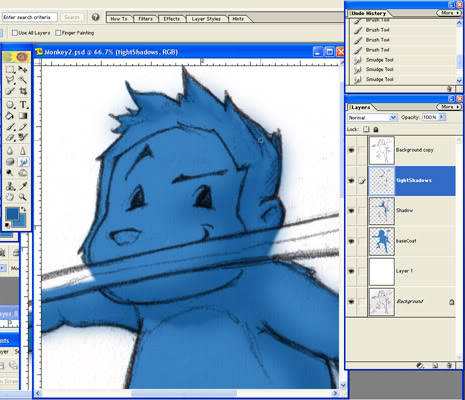

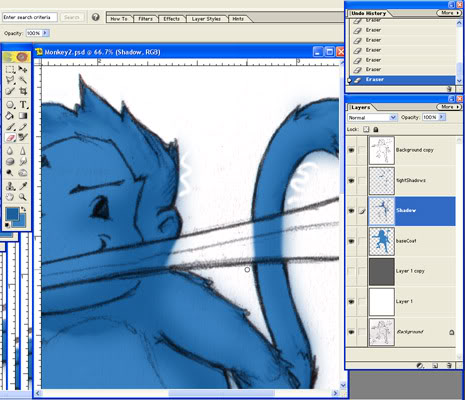

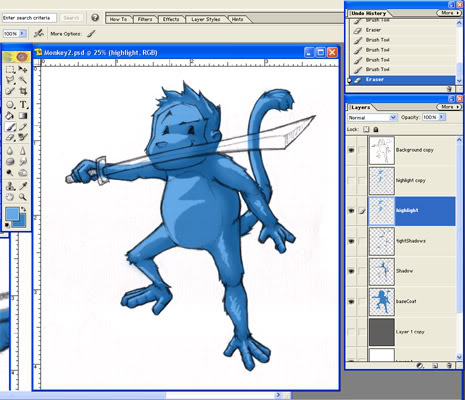

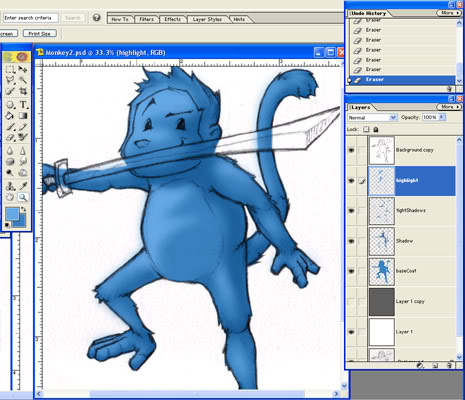

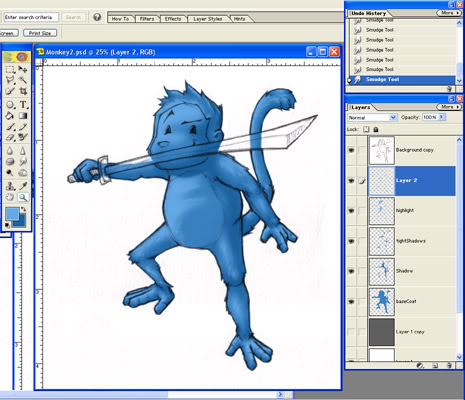

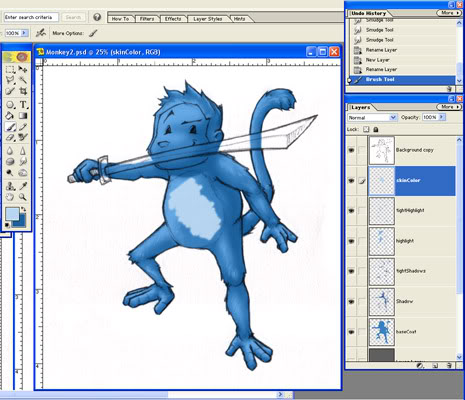

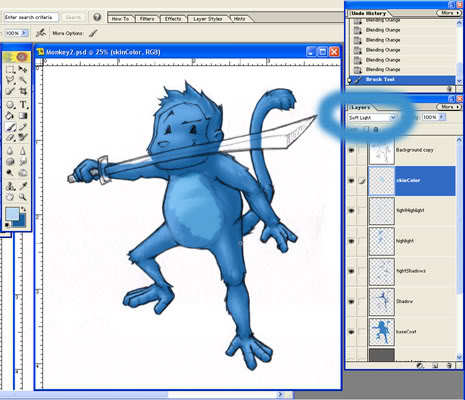

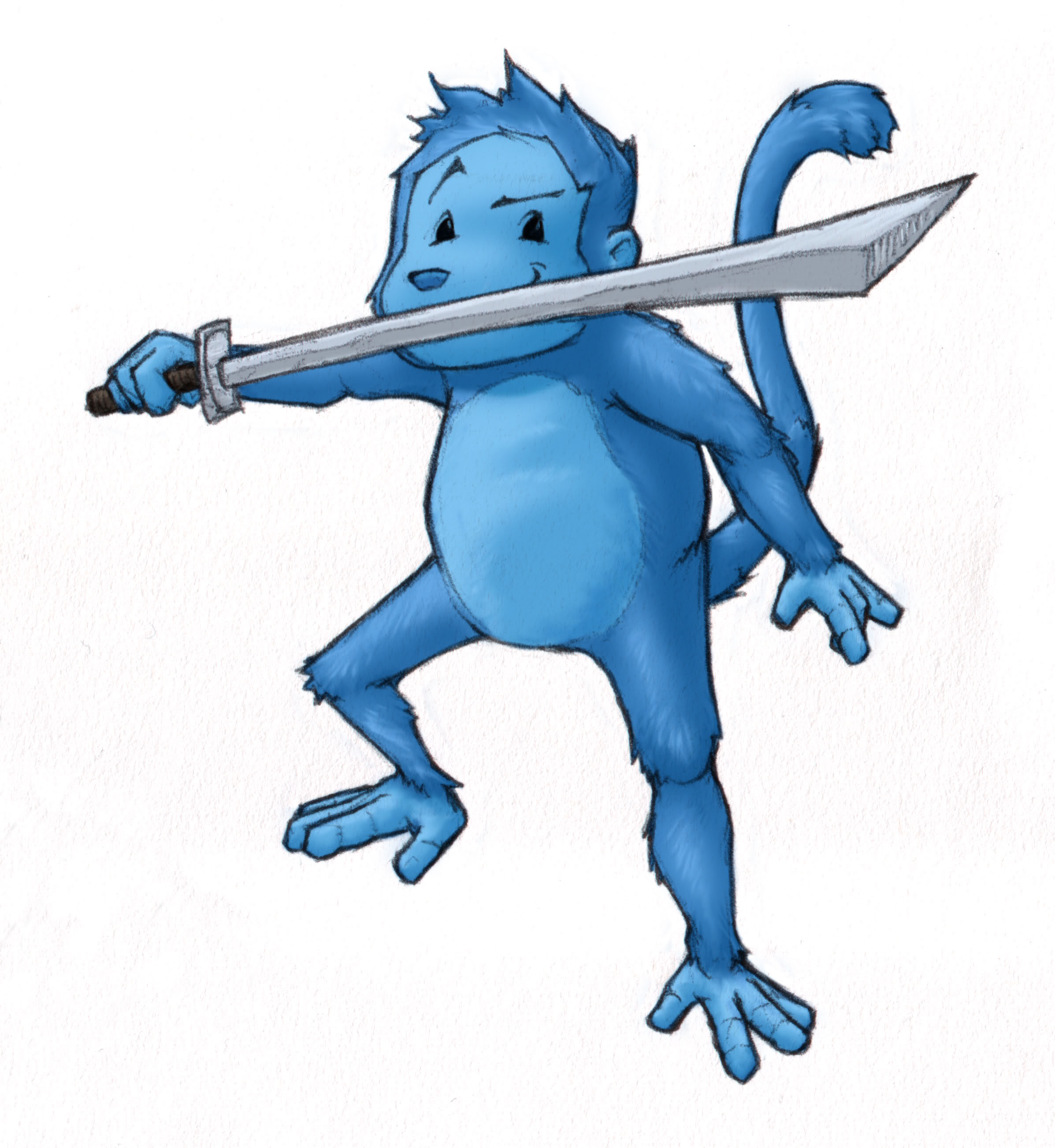

Dustforce and Dust are platformers, each with their own twist. Dustforce is a highly skill intensive, flow-based time-important game with retro visuals, while Dust is a “metroidvania” with a focus on appealing “Disneyesque” visuals and intricate combat. Both are 2D games, with excellent production value in their chosen style. Dust is also notable for being produced almost entirely by a single person.

Dustborn, on the other hand, is a 3D adventure sort of game, heavy on sociopolitical messaging and narrative. It has a modern cartoonish visual style, and it was partially financed by political organizations.

Gamalytic is a website that estimates sales numbers for games, and Steamdb.info also has some useful data. With a quick perusal of those sites for these three Dust games, we can see that Dust ($5,000,000) is the clear winner, Dustforce ($400,000) has met with good success, but Dustborn ($100,000) is less successful.

Gamalytic Dust: An Elysian Tale

Steamdb.info Dust: An Elysian Tale

For how long it has been out, Dustborn certainly has time to catch up with the others, so we will see what happens in the longer run. In the meantime, reviews are another consideration. Dust: An Elysian Tale is well loved, Dustforce DX is likewise popular, but Dustborn is less appreciated. Word of mouth has been unkind to Dustborn, largely because of the polarizing nature of the political messaging that it offers.

The political nature of Dustborn is a recurring theme, with politics being a problem with Ubisoft’s pending Assassin’s Creed: Shadows and Bioware’s Dragon Age Veilguard. These games all embraced sociopolitical themes and pushed political agendas as a key component of game design and promotion. Veilguard may yet spell the end of Bioware, Dustborn could end the otherwise decent career of Ragnar Tørnquist, and Ubisoft is likely to have a rough time with the pending launch of AC:Shadows on top of a string of recent underperformers.

This sort of political agenda naturally limits the sales of games. Dust and Dustforce had no political ties to the real world. They were crafted as games first, not vehicles for outside agendas. Their potential audience is therefore much larger than games that aim specifically for adoption by sociopolitical niches. The “Sweet Baby Inc.” effect has made mainstream gamers less interested in such political games.

Writ elsewhere, this sort of sociopolitical posturing has disrupted Disney and almost every other major Hollywood studio, literature and other entertainment. Writers and producers who see their products as political vehicles are naturally seeing smaller audiences. Setting aside moral arguments for or against using art mediums for political grandstanding, the natural stifling effect of this approach has predictable results. Western entertainment is falling apart, and many developers don’t even seem to understand why, preferring instead to blame customers.

This, then, is where I’d draw a distinction between the desire to make games, and the desire to make money making games.

Video games are an art medium, perhaps the best one for audience agency and end customer customization. They have vast potential for storytelling and play experiences. As with any art medium, they can also be used for less ambitious projects, propaganda and vulgarity. This is inherent to art, part of the human condition, and wholly expected of any avenue of human expression. As such, if your aim is simply to make games, what is considered “in bounds” is entirely up to you. Dustborn and games in its political stable were made to push or embrace certain ideas, and gameplay was a secondary consideration, merely the vehicle for the messages. Dust and Dustforce were made as games, with the play experience itself as the goal for the customers.

Notably, these two latter titles, designed as games first, with a much larger potential audience, have found financial success. They helped their creators make money making games. Dustborn, on the other hand, is less effective at making money, but is an effective title, inasmuch as it embraced and embodied its sociopolitical agendas, with little regard for what customers might want. It’s doing what it set out to do, but one big trouble is that such actions curtail widespread interest.

This, then, becomes the question that game developers (and Hollywood and other entertainment producers) need to look at when they put together their productions. Highly honed games, with a focus on how the game plays, will naturally have more financial success than a roughly equivalent game that naturally limits its potential player base due to political presentation. Are you, as a creator, trying to make something that pushes your views out into the world, or are you hoping to entertain customers and earn their money, and maybe even loyalty? Sometimes it’s possible to do both, but more and more, customers are becoming sensitive to agendas of any sort, and in many cases, rejecting them. Games that are built for the play experience first (and only) are much more likely to be profitable, and effective at building brands and possibly even careers.

Which way, then, my fellow developers? Do we embrace the dusty path of making messages in a unique medium, or do we make games for gamers who wish to shake the dust of daily drudgery off of their weary souls?